Frontier Sciences

Shinichiro Maruyama

Small Symbiosis, Big Impact

“I want to change the world, like he did, into one that can make that crying person laugh.” *¹

This is a line from the lyrics of “Yoake no Uta” (meaning “Song of the Dawn”) by the rock band called ZOOKARADERU. I don’t have any grand ambitions like really changing the world or winning the Nobel Prize. However, just like the lyrics say, I spend my days hoping to do something interesting—some fun research that will make “that crying person” laugh.

Shinichiro Maruyama

Associate Professor

Division of Biosciences

Department of Integrated Biosciences, Laboratory of Integrated Biology

https://purple149824.studio.site/HOME-EN

I am studying the mechanisms of symbiotic relationships among organisms. I have always had a hard time socializing with people, and it is no exaggeration to say that my research on symbiosis is related to my bitter past, in which I have always envied other living things that live in harmony with each other in the natural world. An exaggeration, perhaps? No... yeah, it’s still an exaggeration. I literally said too much. That’s not the case at all. Well, it is true that I am not good at socializing, but that is not why I started studying symbiosis. Furthermore, we cannot tell from the appearance alone whether organisms are living together in harmony. It is only human ego that makes us envious of them.

Our goal is to uncover the scientific mechanisms underlying symbiotic relationships between photosynthetic microorganisms and their hosts—commonly referred to as photosymbiosis—and articulate these processes in molecular and evolutionary terms, beyond everyday language. To this end, we are conducting research using diverse biological systems, including host organisms such as corals, sea anemones, hydra, and amoebas, along with microalgae that live symbiotically within them. For example, how do microalgae, known as symbiotic algae that live in corals, transfer sugars—a product of photosynthesis—to their hosts? This simple question led to investigation, which further led to the discovery of a new pathway by which algae release sugars outside the cells. The level of activity of this pathway is such that the surrounding environment is affected by changes in activity, regardless of whether a host organism is present or not. In other words, for the coral symbiotic algae this is simply a part of their environmental response. However, for the surrounding organisms, it is like a windfall, allowing them to enjoy some crumbs. It is thought that this exchange of nutrients, which occurs as a kind of force majeure, is the key to supporting the establishment of symbiosis. Studies are investigating the environmental conditions under which microalgal symbiosis enhances host-organism growth rates and how such benefits may serve as evolutionary drivers for the development and persistence of symbiotic relationships. These are merely weak interactions between tiny organisms; however, if we zoom out and look at them from a distance, we can ask the question of how the carbon dioxide fixed by microalgae through photosynthesis flows within the ecosystem. Controlling carbon flow is the key to establishing symbiosis. It can be said that it creates the individuality of each symbiotic system and shapes the diverse carbon flows in the ecosystem.

Research results to date have only provided a handful of hints and are far from fully understanding the mechanisms of symbiosis and the carbon cycle within ecosystems. Still, I find myself honestly saying “This is fun!” I enjoy my research every day, vaguely thinking that if I continue to do what I think is right, the world might change just a little someday.

“I can’t do anything.

Is it really something to be proud of that I even noticed?

There are nights that never end

in my head”*²

*¹ *² Excerpts from the lyrics of “Yoake No Uta” by ZOOKARADERU, translated into English by the author.

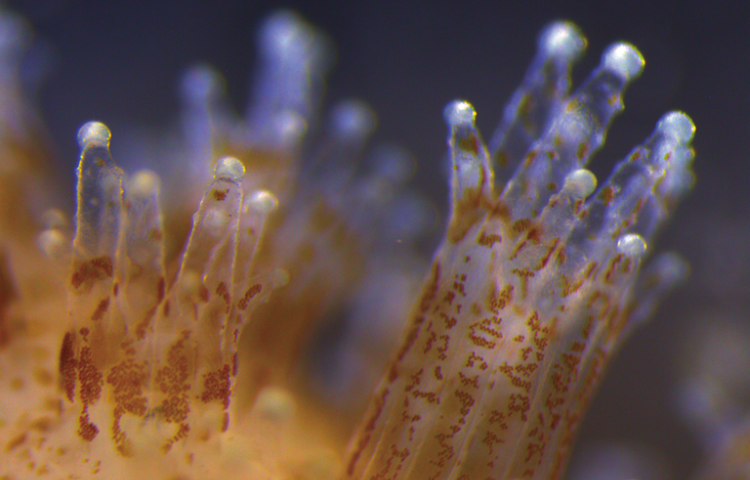

Microalgae that live symbiotically within the sea anemone can also be seen through the fluorescence emitted by chlorophyll.

We were the first in the world to develop cutting-edge technology to produce “bleached” amoebae by removing symbiotic green algae from photosymbiotic amoebas. Photo by Daisuke Yamagishi

We are focusing on the life of the green algae that live symbiotically in the slightly greenish eggs of the Japanese black salamander. Photo by Colin Anthony

If you look closely at the polyps of the cauliflower coral, you can see brown dots, which are coral symbiotic algae. They are key players in unlocking the secrets of endosymbiosis.

vol.46

- cover

- Fusion Energy

- Discussion Meeting

- Research Examples at the Transdisciplinary Fusion Energy Center

- Topological Quantum Materials Realized by Molecular Beam Epitaxy

- Small Symbiosis, Big Impact

- Life of Fish Roaming in the Vast Ocean

- GSFS Front Runners: Interview with an Entrepreneur

- Voices from International Students

- On Campus/Off Campus

- Events & Topics

- Awords

- Information

- Relay Essay